Many companies pay staff with share-based compensation, which generates real costs to shareholders. Yet some companies and Wall Street analysts tend to omit these expenses from earnings by issuing “adjusted earnings” that often distort a company’s historical earnings, future potential and free-cash-flow metrics.

Share-based compensation provides employees with salaries in equity such as a company’s own stock, warrants or stock options. While salaries paid in cash are different from payment in equity instruments or shares, both are ways to compensate employees for their services and involve a transfer of wealth from shareholders to employees.

There are pros and cons to share-based compensation. It can help incentivize staff to work hard and deliver great results for their employers and can help attract talent in a competitive job market. Stock-based comp can also help finance growth by freeing up cash for new business ventures. However, given the volatility of share prices, paying in stock also adds risks for employees and companies. Whether a company pays employees with cash or equity, both forms of compensation are a real expense that we believe should be reflected in company earnings.

Accounting Models Can Help Estimate Costs

Today, that isn’t the case. It’s common practice for equity analysts to simply remove this equity-linked cost from their calculations. By doing so, they adjust the company’s costs lower, which bolsters the case for a higher net income projection. While we don’t always know in advance the actual cost of issuing equity-linked compensation, scholarly models like Black-Scholes can be used to estimate the “fair value” of such instruments. US GAAP and IFRS require companies to use such models to estimate the cost of share-based compensation, and we subscribe to this view.

We believe that stock-based compensation should be analyzed as a two-way transaction. The company hands over something of value to the employee, who in turn finances that expense (by becoming a shareholder). This is exactly as if the company sold shares in the market and handed over the proceeds to the employee.

With more stock in the market, shareholders’ equity will be diluted. As an investor, you need to consider both the historical equity-linked compensation by using diluted share numbers and the future potential dilution from the continued issuance of equity-linked instruments.

More Companies Are Paying Salaries in Stock

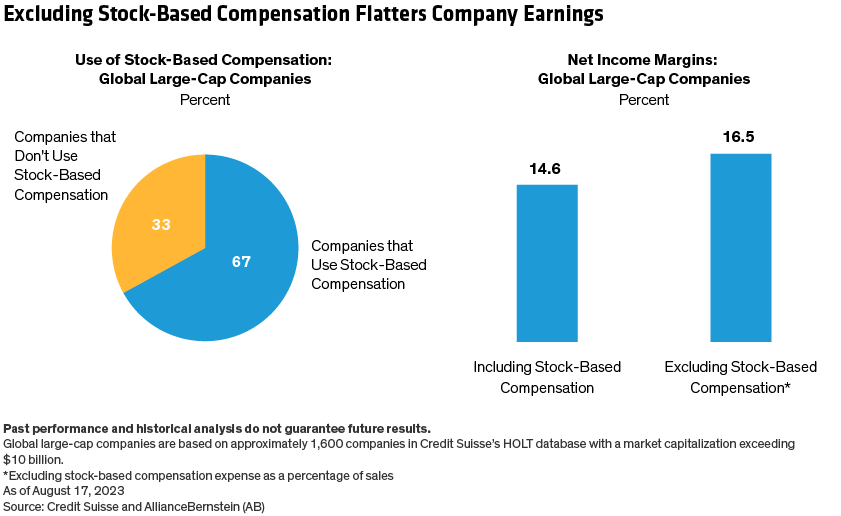

The “adjusted earnings” omission is relevant to hundreds of companies around the world. While companies in the information technology and communication-services sectors use stock compensation the most, the practice is gaining traction in other sectors, too.

Today, about 67% of global listed companies above a $10 billion market capitalization use stock-based compensation, according to data from Credit Suisse HOLT. Within that group, companies spend about 2% of revenue on average on stock-based compensation post-tax (technology companies spend more than 4%). As a percentage of sales, stock-based compensation makes up almost five times more today than it did in 2006, according to research by Morgan Stanley. Since the average company’s net income margin is 14.6%, about 15% of earnings are not considered a cost. That’s because by removing the stock-based compensation, the net income margin is inflated to above 16.5% (Display).

Adjusted numbers always deserve scrutiny. If an adjustment inflates net income, it also skews the valuation. We believe that free-cash-flow models provide a more robust method of valuing investments. However, cash-flow estimates are also subject to these adjustments, as stock-based comp is added back to the adjusted operating cash-flow metrics. Here again, investors need to watch out—in particular with early-stage US tech companies. These companies often represent themselves as profitable, but in reality are financing their growth through share-based, compensation-linked capital raises. Many of these companies spend more than 20% of their revenues on stock-linked compensation, eating up earnings entirely.

Better Numbers Lead to Better Decisions

Pretending that stock compensation isn’t a real cost adds uncertainty to an earnings outlook—and undermines the purpose of projections. Analyst forecasts should help investors make better decisions by providing a transparent outlook of a company’s future. In this case, we believe that adjusting for stock compensation creates unnecessary uncertainty and complexity in a world that has more than enough uncertainty to begin with.

Investors should be wary of adjusted net income figures because they make valuations look too attractive. It also makes it much harder for us to compare valuation multiples between companies that do and companies that don’t use share-based compensation.

Research and valuation should always start with reported net income numbers rather than adjusted numbers that don’t reflect a company’s true outlook. We encourage Wall Street analysts to avoid making unhelpful adjustments to earnings forecasts; that would provide a robust foundation for generating better outcomes for clients. Investors who monitor their portfolio holdings should verify that company outlooks reflect complete pictures of the business’s revenues and expenses—including those costs that some analysts conveniently choose to ignore.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to revision over time.